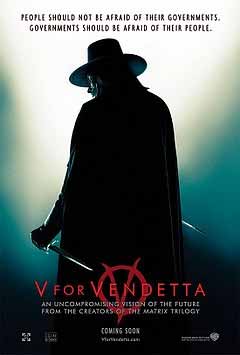

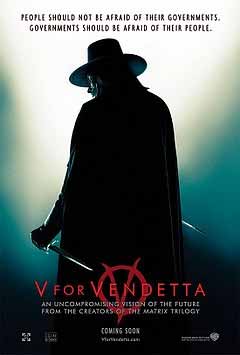

V for Vendetta

As a long-time political conservative I find it more than a little ironic that I am recommending that everyone see V for Vendetta and take it seriously. My prejudice going in, of course, was in line with all the "this movie glorifies terrorists" criticism that's about on the net. Still, between the Wachowski brothers, Natalie Portman and Hugo Weaving, and the look of the thing in the promos, I decided I had to see for myself whether it made heroes of soulless killers. I'm so glad I made that choice. I don't mean that V is not every bit the leftist-paranoid-conspiracist cry for help that some allege it to be, for it most certainly is exactly that. But there is an artfulness to the telling of the story and the asking of some uncomfortable questions that is worth the time and consideration of all citizens. I could give you a detailed breakdown of the artistic merits of the movie — i.e., the acting, the script, the visuals, etc. — but other reviewers can do that. I want to talk about how V affected me as I watched it.

As a long-time political conservative I find it more than a little ironic that I am recommending that everyone see V for Vendetta and take it seriously. My prejudice going in, of course, was in line with all the "this movie glorifies terrorists" criticism that's about on the net. Still, between the Wachowski brothers, Natalie Portman and Hugo Weaving, and the look of the thing in the promos, I decided I had to see for myself whether it made heroes of soulless killers. I'm so glad I made that choice. I don't mean that V is not every bit the leftist-paranoid-conspiracist cry for help that some allege it to be, for it most certainly is exactly that. But there is an artfulness to the telling of the story and the asking of some uncomfortable questions that is worth the time and consideration of all citizens. I could give you a detailed breakdown of the artistic merits of the movie — i.e., the acting, the script, the visuals, etc. — but other reviewers can do that. I want to talk about how V affected me as I watched it.

In its overall tone, V for Vendetta reminds me of nothing so much as A Clockwork Orange, by which I mean this film reminded me of Stanley Kubrick at the height of his powers. As I recall, Clockwork was criticized at the time for glorifying the violence of English hooligans, but it was still a compelling and artful movie. The Matrix brothers, Andy and Larry Wachowski, have done it again. V is The Testament to the time in which we live, post-9/11, just as the first Matrix was for the '90s. There are several places within the story arc of V where the politics gets a bit thick, but there is only one genuine lacuna in the plot. The problem with that sidetrack is that it wanders too close to current reality, and by leaving the ambiguous and fantastic future realm the movie so carefully constructs, it also loses the magic of the moment. Fortunately, the story recovers itself quickly and returns to the literate fable it intends to tell.

Now I will give you as close as I care to get to a spoiler: I think the reason V succeeds as art where other, like-minded films fail is that V is at its heart the story of a steadfast cop (Stephen Rea as Finch) working to solve a crime; it is a police-crime drama set in a charged political environment. As a friend explained, V may be the protagonist, but that doesn't make him the hero. The hero of V is the good cop after all.

Natalie Portman has entered the pantheon of my personal goddesses for her Evey. Perhaps only an Israeli born in Jerusalem, as Portman is, could give such an unflinching portrayal of the evolution of a terrorist. Hugo Weaving, by force of personality and voice alone, behind that ridiculous mask, does make V the dashing freebooter, a romantic figure. V and Evey engage in this long, elaborate, alchemical dance with each other. As she becomes more and more a cold-eyed terrorist, V begins to doubt. Doubt is death to a fanatic, salvation to the true hero. Ultimately, because of Evey, V manages a sort of personal redemption, at the ultimate cost. And in the end, it is not even Evey's decision, but the tide of history turning, represented by the multitude swarming the citadel, that wins the day.

Ok, that's the kudos. Now for the caveats. Well, the first I have already alluded to above, when I mentioned this long, mid-story diversion. It is almost an accidental, unintended portrait of how a real terrorist is formed in the seething caldron of our present world. Evey's sojourn in the concentration camp seems a false and flawed eddy, necessary only to introduce a spurious gay-martyr thread into a story line already veering dangerously close to the ham-handed. As it turns out that this whole episode is the concoction of V, and not the handiwork of the secret police, it tells more about how evil men can prey upon the vulnerable souls at the margins of civilization than it perhaps intended to do. (Oops, sorry, another spoiler.)

The greater problem with V for Vendetta is that it is not nearly so clever, literate and careful in portraying the opposition. John Hurd gives a very disappointing performance, literally one-dimensional, as the fascist tyrant. The forces that turned his Adam Sutler into the stereotypical Hitlerian figure are simply assumed, a given acknowledged only by a brief expositional soliloquy, told from V's point of view. This to me is a great problem with all liberal argument against incipient fascism. The fascistic impulse roiled most of the 20th century and shows no sign of abating at the dawn of the 21st. Yet I know of no artist in any genre who is even trying to understand that historical impulse with the same care given to understand, and by implication to excuse, the Islamofascist threat that is the real menace in the world today. In the leftist mindset, the West is always wrong, even though it is only in the supposedly benighted West that works such as V for Vendetta could be made. V goes to great lengths to equate followers of the Muslim religion with the most oppressed victims among us, without the slightest acknowledgment of how Islamic theocracies routinely treat women, homosexuals, and all the other special classes of persons of such concern to liberals. Excuse my vulgar language, but V for Vendetta is a movie that pisses on the grave of Theo van Gogh.

One of the reasons I became a political conservative in the first place was because I reached a point as an adult where I could no longer live with the logical conflict that exists at the heart of the left-liberal political paradigm. While constantly crying out against the oppressiveness of the presumed fascistic state, every solution sought and offered by the left is yet another extension of the same state power they incessantly deride. It is historically demonstrable that the constant resort to state-sponsored, collectivist programs to solve social problems is what leads inexorably to fascism and genuine oppression. Likewise, in my opinion, modern liberalism is so infected with the doctrine of moral relativism, which really amounts to a fear of making judgments about anything, that it is unable to deal with anything larger than a protest march in an effective manner. It is, however, the reliance on moral relativism that necessitates seeking government intervention into spheres that are not the rightful realm for political or statist action. Leftist theory also allows for a great deal of intellectual laziness, and the logical flaw at liberalism's core is the first proof of that. All of which has a great deal to do with why regular people, as opposed to liberal intellectuals, are so willing to support what looks to liberals like a Hitler-wannabe, rather than the liberals' preferred, elitist will-o'-the-whisp. People are not the sheep liberals like to imagine they are. What looks like a fascist to a liberal, looks remarkably like salvation from condescending, touchy-feely fascism to the rest of us.

This then is what I see as the critical flaw in V for Vendetta: While it very artistically goes to great lengths to craft a sympathetic portrait of the terrorist V, including greatly downplaying the bloody consequences of the blind violence of the terrorist bomb, the movie renders the forces against which V contends as flat, one-dimensional stereotypes. I have already mentioned the political element, but there is an even more disturbing attack on the dominant religion of the West, Christianity. I freely admit that the Catholic Church fully deserves the bashing it gets here because of the way it has so badly mishandled the pedophile priest scandal in the U.S. and elsewhere. And the portrait of the television preacher, the fictional Prothero, is justifiably unflattering. Nevertheless, having lived in the San Francisco Bay Area long enough to qualify for "native Californian" status, I have had occasion to rub elbows with my fair share of liberal artists, and I never fail to be amazed by the cultural myopia they exhibit in their reflexive hatred of Christianity.

Can we pause to remember that it was the dominance of Christianity, and no other of the world's religions - not Islam, not Judaism, not Buddhism, not Hinduism - that gave birth to the Enlightenment in Europe? It was the Enlightenment after all, and all those "old, dead, white guys," who thought up the idea that we human beings are all equal, and thus we all have rights. In fact, no other of these religions could have given birth to anything remotely resembling the Enlightenment, and here's why: Being a pagan myself, I often wondered why Christianity triumphed in Europe. I found the answer, oddly enough, in the pages of Robert Graves' book on Celtic poetry, The White Goddess. Graves contends and I agree that Christianity triumphed, despite the anti-Nature and anti-woman elements that developed within its institutions, because it promised universal salvation, an eternal life for ordinary Joe's and Jill's. This radical doctrine shattered the old order that offered eternity only to the King/Pharaoh and a few of his courtiers, perhaps. Pre-Christian paganism can be rightly described as elitist, with salvation and eternal life reserved exclusively to the Initiates. The message of Jesus that we are all children of God, and by following his teachings all can go to paradise, was in its time a truly revolutionary idea, a message strong enough to conquer the Roman Empire, in the person of the Emperor Constantine, and thus to conquer the then known world. From this core message came the later political revolution we call the Enlightenment; and from the Enlightenment came the political freedom so much enjoyed by modern leftist artists to abuse church and state, while romanticizing terrorists and foreign ideas that directly threaten all of us now.

Until artists like the makers of V for Vendetta get over this historical and cultural myopia, their very legitimate proposition that "people should not fear their governments, governments should fear the people" will not hold the appeal for the folks, for ordinary citizens that it otherwise would and should hold. However, having myself meandered into a bit of political polemic, let me try to wander back toward cinematic criticism. Is V for Vendetta a transcendent work of art? Yes, I think it is despite its flaws. The fact that it inspired me to write all this is a small proof of its artistic power. I do think V is the best treatment of its topic that we are likely to see for some while. I do think that it should be seen. If the questions it asks, somewhat stridently maybe, somewhat myopically certainly, are nevertheless uncomfortable to all of us right now, that is a good thing. Because if we don't all, individually, grapple with the questions V poses, our civilization will be lost. I believe that would be a tragedy.

Copyright © 3/27/06, Erin Iris Earth-child

As a long-time political conservative I find it more than a little ironic that I am recommending that everyone see V for Vendetta and take it seriously. My prejudice going in, of course, was in line with all the "this movie glorifies terrorists" criticism that's about on the net. Still, between the Wachowski brothers, Natalie Portman and Hugo Weaving, and the look of the thing in the promos, I decided I had to see for myself whether it made heroes of soulless killers. I'm so glad I made that choice. I don't mean that V is not every bit the leftist-paranoid-conspiracist cry for help that some allege it to be, for it most certainly is exactly that. But there is an artfulness to the telling of the story and the asking of some uncomfortable questions that is worth the time and consideration of all citizens. I could give you a detailed breakdown of the artistic merits of the movie — i.e., the acting, the script, the visuals, etc. — but other reviewers can do that. I want to talk about how V affected me as I watched it.

As a long-time political conservative I find it more than a little ironic that I am recommending that everyone see V for Vendetta and take it seriously. My prejudice going in, of course, was in line with all the "this movie glorifies terrorists" criticism that's about on the net. Still, between the Wachowski brothers, Natalie Portman and Hugo Weaving, and the look of the thing in the promos, I decided I had to see for myself whether it made heroes of soulless killers. I'm so glad I made that choice. I don't mean that V is not every bit the leftist-paranoid-conspiracist cry for help that some allege it to be, for it most certainly is exactly that. But there is an artfulness to the telling of the story and the asking of some uncomfortable questions that is worth the time and consideration of all citizens. I could give you a detailed breakdown of the artistic merits of the movie — i.e., the acting, the script, the visuals, etc. — but other reviewers can do that. I want to talk about how V affected me as I watched it.